The Kestrel 4000 – Post-Kona Review

The bike expo in Kona this year was kind of a letdown. Last year, the thing was lousy with new bikes: P4, Fuji D6, Scott Plasma II, Ridley Dean, QR cd0.1, Look 596… This year? Nada but for the Kestrel 4000 and the Specialized Shiv. The Shiv is far from a mainstream design and will only be available and suitable for a relatively few riders with its limited sizing and astronomical limited edition pricing. It was nice to see in the flesh, including Fabian Cancellara’s personal Shiv in the SRAM booth. But the 4000 was the only “mainstream” new offering on display.

Kestrel had two 4000’s in Kona – both unrideable prototypes. One was the big $$ LTD model, but the other was the SRAM Red-equipped Pro which will sell in the P4-like $6k range. There should also be a cheaper version with Ultegra. This was my first opportunity to see the 4000 in the flesh, and I was not disappointed. I think the release of the 4000 this Spring could be a great move by Kestrel. At a time when more than 25% of the bikes on the pier were from one manufacturer (and perhaps deservedly so), many athletes are looking for something different. And almost no one else has anything interesting to offer them this year.

Talk to any old-school tri geek, and chances are they owned an original pre-1990 Kestrel 4000 ems or had a buddy that did. These Trimble-designed bikes were ground-breaking with their full carbon monocoque (one piece) frames and aero tubing profiles. This was followed by the original Km40, one of which I have sitting in my basement.

Lis rode this bike for years, and it was more or less a P2c – more than a decade before the P2c came out – 78 degree seat angle, aero carbon tubes (note that it did use the then standard 650c wheels and had an overly tall head tube). Any tri-fogey will tell you that for maybe a decade, Kestrel was THE tri bike to have. They were simply ahead or everyone else. For sure, Kestrel lost their mojo through the early 2000’s as it changed ownership, but brand manager Steve Harad is doing his best to remedy that situation under the umbrella of Fuji-owner Advanced Sports. I think it’s a great idea for Kestrel to recall their roots by naming their latest high-end tt offering the 4000, and we’ll see if this bike becomes an icon like the original 4000. My early observations indicate that it has a shot.

First off, you need to understand that the 4000 was designed to be UCI-legal for time trials. As I have mentioned several times in past articles, many manufacturers are realizing that they need different designs for UCI-TT bikes and tri bikes, even if their tri bike is UCI legal. Kestrel’s (the Airfoil) is not UCI legal, due to the missing seat tube. The UCI requires a “double diamond” frame design, which killed the use of beam bikes in the mid 90s (Anyone remember Bjarne Riis hucking his Pinarello beam bike into the bushes in a TDF time trial? Very prescient of him…). The UCI requires a bunch of other garbage too – anything beyond a 1950’s steel road frame is considered “technological drift” – but don’t get me started. The other issue is that Pro Tour TT riders require bikes that allow them to adopt super-aggressive positions and handle well at 30+mph under 450 watts of hammering – but only for a few minutes to an hour. As opposed to triathletes, these guys are willing to adopt extreme positions in many cases if it will shave a few seconds – comfort is not a requirement and running certainly isn’t a consideration. Needless to say, an Ironman bike and a Pro Tour prologue machine must each serve very different masters.

On the surface, the 4000 looks like an Airfoil with a small seat tube added, tucked tightly around the rear wheel. But look closer and you’ll notice the brake treatments, the virtual seat mast, sculpted chain stays, beefy seat stays, blended fork, and the more extreme geometry (at least in the larger sizes). Let’s look at each of these individually.

The front brake on the 4000 is similar to the center-pull cantilever design used on the Specialized Transition. This eliminates the need for aerodynamically-dirty front brake cable housing, and allows an overall cleaner front end. Kestrel employs a dropped cable hanger, which will allow you to run the stem with no spacers and not interfere with the brake cable (an issue with the Transitions). The rear brake uses the same cantilevers mounted under the chain stays, a configuration that is becoming commonplace. The chain stays show some interesting sculpting which according to Harad were a missing piece in the aero puzzle and gave noticeable drag reduction.

The hidden rear brakes and dropped seat stays allow a very clean trailing edge up to the virtual seat mast and saddle. The notched trailing edge of the seat tube gives the bike a bit of a jet fighter look. It will be interesting to see how this design affects lateral and vertical stiffness.

Now, in my opinion the integrated seat mast is one of the the all-time stupid bicycle “innovations”. For the sake of a few grams and maybe some extra stiffness, you get a frame with potentially reduced resale value, limited adjustability, difficult to fit into a bike case or car, and with a high “clench factor” every time you have to set one up for someone. There is nothing quite like the feeling of hack-sawing a brand new $5000 bike to size. The mast clamps have very limited adjustment ranges, and if you make a mistake here it’s new frame time. Who needs it? Not Kestrel – the 4000 uses a unique multi-part virtual seat mast. It does require trimming of the exterior sleeve, but the consequences of mis-cutting here are no more than mis-cutting a seat post. Once you have the thing set, the whole shebang pops off the frame with one screw, and you don’t have to worry about saddle height – its stays set unless you change the setting inside the removable mast. The head of the seat post is a Ritchey unit with sliding rail that allows a good deal of fore-aft (seat angle) adjustment. The mast looks to be set at a slack 74-75 degree angle (in a nod to the UCI) but the adjustable head will allow steep positioning.

The seat stays depart from the super thin blades seen on other manufacturers’ bikes – they are very thick and join the “seat tube” in an unusual hip-like structure similar to that used in the Airfoil. Certainly they should be quite stiff, but one might question how aero they are. The wind tunnel results seem to indicate that they are plenty slippery. The front fork has a very similar shape to the seat stays and the crown blends smoothly with the frame – another feature becoming common these days on TT bikes. Overall you get impression that the rear triangle should be quite stiff. Unfortunately I was unable to confirm this as the prototypes were unrideable. Production was slated to begin as we speak though, with bikes hitting our shores by early Spring.

The geometry (stack and reach) of the 4000 is somewhat unusual as listed on Kestrel’s website. The stack varies very little from size to size, making the larger bikes VERY low in front. However, I have been cautioned that this is not set in stone yet so we’ll have to wait to see how the geometry shakes out. Expect it to be aggressive though (low stack, long reach).

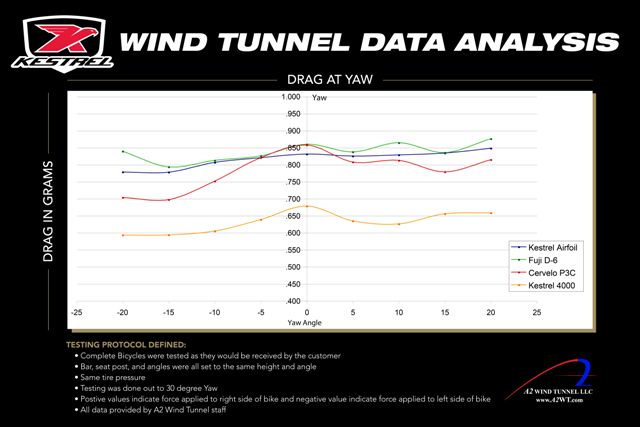

What about the wind tunnel? You may have seen the data that Kestrel released a few days before Kona. If you’re a major geek with lots of time on your hands, you may also have read the 10-page thread on the ST forum about this data. If you sift through the name-calling, off-topic posts, I’m-smarter-than-you-about-aerodynamics battling and pure unadulterated speculation (i.e., a typical ST thread), you will learn almost nothing. If the above were removed, it would number about 15 posts, including a few good ones by Mark Cote of MIT/Specialized. The quick summary: the Kestrel results are not entirely consistent with other manufacturers’ data. Lots of folks are skeptical because the 4000’s results look very very good. But a non-biased insider present during the tests claims that they were done very fairly and the 4000 kicked some butt. Steve Harad stands behind the data and is willing to have it confirmed independently. There, I saved you 2 hours. All that aside, the frame is likely pretty darn aero. It may or may not be as good as a P4 or Shiv, but it’s probably in the same class. It was designed in the tunnel, so Kestrel had the opportunity to tweak the design to get it as aero as they could (sculpted chain stays for example). Why no P4 in the tunnel data comparison? Harad says it’s because the P4 as it comes out of the box is not UCI-legal – note that Cervelo Test Team was running them with jury-rigged Elite aero bottles in place of the nifty (but not to the UCI) integrated bottle/tool kit/stiffener.

The elephant in the room (and in most wind tunnel test rooms)? No rider on the bike during testing. Could change things a lot, better or worse, due to frame/rider interactions. This is true for any frame, and it is definitely tough to make inter-frame comparisons with a rider because of the added variables and noise. The rider’s position must be controlled carefully and be identical on all bikes. However, this data is supposed to be coming out soon – can’t wait. Net-net, the 4000 will likely be in the same league as the other top-end aero bikes out there, maybe a bit more aero, maybe a bit less, but you will probably be just as fast on it as you would on any of these other bikes assuming same fit. Just remember, if your position stinks, any difference in frame drag will be far overshadowed by body drag.

So if you are looking for a new high-end aero bike and something a little different appeals to you, keep the 4000 on your radar screen. Final geometry is still a question, and that will of course determine if this bike is a good option for you. Lateral stiffness, handling, and ride quality also remain to be seen. I will post more info here as I get it, and hopefully as I get to ride one.